Is there another way to think about the political cycle?

Politics always goes from left to right, and back again. But what else?

Bit on me & why am I starting a substack?

I’m a pollster and analyst - and love identifying and explaining the non-obvious slower trends/patterns that shape societies. I’m the Chief Research Officer of Focaldata - a 60 person AI-research company.

I’ve called this substack The Political Whiteboard because at work that’s basically what I enjoy most. A good whiteboard session between colleagues looking at ideas and graphs. In that vein this substack is about nascent ideas, scrappy charts and offbeat insights, not about creating a fully formed worldview or definitive take on anything. This substack will be free. Feedback is always welcome - be challenging but nice.

What’s the summary? Is there another way to think about the political cycle?

Looking at politics on a broad 2x2 of aggregate left and right shifts over time and the degree to which Labour and Conservatives dominate their own ideological “block” of voters means you can observe the political cycle as an actual loop. If you don’t think you will find that observation interesting - then I’ve just saved you 15 minutes of your time.

What’s the detail?

Firstly, let’s start with how the political cycle is normally captured and visualized - that’s normally via polling averages; specifically line graphs for each political party smoothed over to capture the dynamics of each individual party, with usually Labour (red) and Conservative (blue) lines swapping, with the gap broadly indicating the scale of win or defeat for either side. Below are the screen grabs from Wikipedia.

2024 Election and beyond

2019-2024 opinion polling

The first place to seek a different way to understand polling is to look at the aggregate left and right balance in the country, by which I mean the collective right wing vote (Conservative and Reform/predecessors vs Labour, Liberal Democrats + Green).

There’s all sorts of problems with measuring left-right balance this way, but for the sake of simplicity it provides an interesting picture, and is pretty reflective of when we get a change in government.

Below is my basic visualization of these aggregate right/left vote shares looks like since 1983.

The line graph (Red = left, Blue = right) broadly describes the shape and structure of British politics these four decades - New Labour dominance, the precarious Cameron years, briefly Conservative supremacy under Johnson, and total Tory collapse post partygate. A couple of other things leap out:

The collective left vote is - all other things being equal - higher than the right.

The right today is - collectively - in a marginally better place than the Blair years - recent polling coming out from More in Common and other pollster points to a converge close to 50/50 only months after the left vote was close to 60-70% pre 2024 election. (More on how it is split later)

Volatility is now king. The number of times the aggregate left and right votes have cut across each other is speeding up in frequency.

We know from some great work of others that the left / right dynamic in the country is broadly thermostatic. (Will Jennings helpfully flagged this paper and this paper to me.) Thermostatic politics is the beautifully simple idea that when a government of a particular stripe gets elected, the public in general moves - on issues and voting intention - the other way. Similar, but related to the idea that governments have a “cost of governing”. You invariably do things a certain way e.g. if a left wing government does left wing things like put my taxes and spend more and you incur an electoral cost for actually doing things (why oppositions always get elected after some point)

But, here’s the thing, looking at just the left/right mix of a country misses another crucial aspect of British first past the post politics which is fragmentation. By fragmentation I’m simply referring to the number of people voting for parties who are not Labour or the Conservatives. It’s up - and by a lot with nearly 40% of the electorate headed this way. Couple of things to note

Beyond the chaos of the 2019 European Local elections we’re at a sustained high point for voting for “other” - the political system is at risk of totally unravelling

The degree that the minor parties rise and fall together is really striking. In polling terms the covariance is high - so when Reform and the Greens rise together it’s telling alot about the system

It’s also interesting that Reform/Brexit/UKIP appears to rise and fall much more dramatically than the Greens/LD but…

There are a few periods actually when populist right and fragmented left move in opposite directions (2013-2017). This is really interesting and stimulus for me to look further into how we can think about minor parties and major parties

To think about minor parties (not so minor now) slightly differently I thought about the idea of “Block dominance”. Basically I’ve defined Block dominance as the extent to which Labour and Conservatives dominate their own “red” and “blue” blocks respectively - and compare the net scores between the two blocks.

Definitions:

Right cohort/block dominance = (Conservative monthly polling share / Con + Reform) – Labour / (Labour + LD + Green)

Right_left lead = (Conservative + Reform)- (Labour+Green+LD) Note: I know I haven’t included the SNP

Worked example: More in Common Fieldwork: 19th - 21st November 2024

Labour 25%

Conservative 28%

Liberal Democrat 13%

Reform 19%

Green 8%

SNP 3%

Labour block dominance = 25%/(25+13+8) = 55% Note: I know I haven’t included the SNP

Conservative block dominance = 28%/(28+19) = 60%

Right lead on net block dominance +5%

The end result of plotting monthly polls like this vs aggregate left right shift is very interesting. Britain’s political cycle appears to be driven by thermostatic swing and “block dominance”. The variables interact to create a basic political cycle. The below chart plots each month (a square) from 2010 to 2024, with 2010 being blue, and 2024 deep red, and the colour of each square indicating which time period we are in.

The main thing is that each political cycle is different but eventually the aggregate left right balance of a country and the prospective main party’s block dominance converge to chuck out whichever party the electorate wants out. It’s basically a mild iteration on normal left right swing, but you can see that fragmentation dynamics are literally part of that process - and for me that was the most interesting thing.

By adding in a very unscientific and basic arrow below you can see over time that Britain is in a recursive loop between switching it’s aggregate politics from left to right, and back again, whilst at the same time voters working out how to give the Labour of Conservatives a majority once the country has became in aggregate so left or right wing that voters need to self-sort towards the bigger party to give them a majority.

The Cameron years….

What’s fascinating about the Cameron years is how each month basically flows to the next on this particular pattern. Conservatives scrape in on a small vote share but “owning” their block, in 2010. Over time UKIP becomes a problem with a threat on the Eurosceptic/authoritarian right, but then the right wing block grows in aggregate, and then the Conservative betterment of their block/cohort dominance increases to the extent that he can then win a narrow majority with a totally different political landscape in 2015 vs 2010.

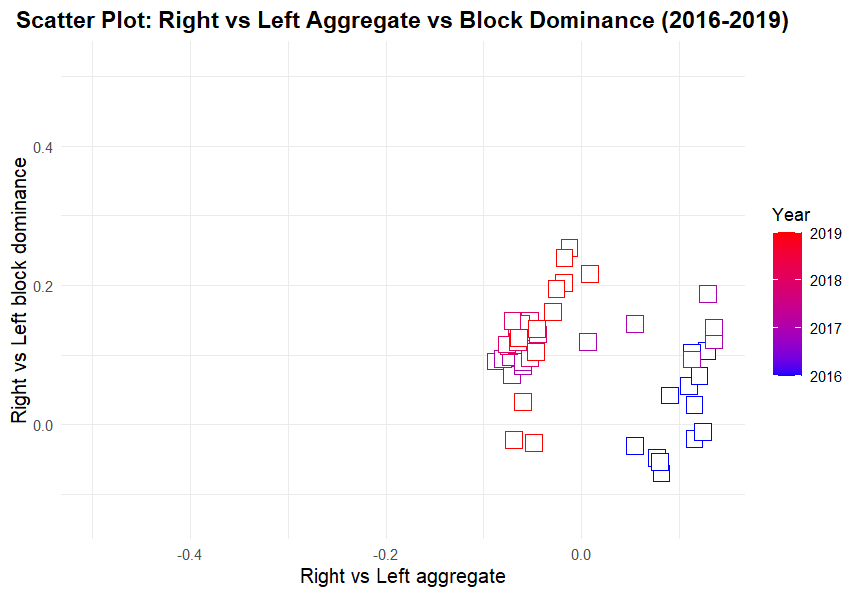

2016-2019

The sheer chaos of the post Brexit years is easily visualized on this model with the massive squandering of PM May’s poll lead in 2017, the rise of Jeremy Corbyn during the campaign, extraordinary 2019 European elections, and subsequent 2019 General Election, it is not possible to divine any consistent pattern using this framework. But it does, slightly confirm to many of us that were analyzing those election what extraordinary times they were.

2020 onwards…

From 2020 onwards the cycle returns, with voter flows moving consistently, almost to the month (I’m not skilled enough to show this trend by month with arrows so just the colour gradient that R does) with a drastic right-left shift first (first part of the loop) with cohort dominance really only kicking in from 2022/2023 onwards. Given the polling error at the 2024 election, it’s unlikely that Labour’s position was ever as strong or has degraded as fast since the election.

If you think about a political cycle (from the perspective of the right - reverse if from the left) this way there’s basically five moments that happen on a repeated cycle:

The win: The country is in aggregate pretty right wing (60%+) and voters give enough votes to the main right win party (historically the Conservatives) a majority. E.g. 2019.

The shift: The Conservative party dominates its “block” of voters no more or no less than Labour, but in aggregate the left starts to be equal or bigger as a group as the costs of governing kick in and the thermostat shifts. This is when the arrow moves horizontally left across the graph without changing on the vertical axis (e.g. 2010 - Con largest party no majority, 2017 largest party no majority).

The slide: Once a country has moved in aggregate against you and can move no further (let’s say 60-70%+ for the left block) block dynamics take over - Labour starts to take a greater percentage of its enlarged block, and the opposite happens to you. You bleed to the right. This always ends in defeat. E.g. 2024.

The reverse shift: You are still not in control of your block as you historically have, but the thermostat and costs of governing shift against Labour. Both main parties hold a disappointing % of their blocks. This isn’t terrain to win convincingly, and if you don’t shift enough there’s a problem (interestingly the 2015 Conservative victory feels similar to this, but arguably also 2005) → I think where we are today.

The ladder: The electorate have moved as right as they are going to. The government needs to change, so voters self sort to ensure Labour are not near the levers of power. → Leading to the win.

What are the takeaways from looking at politics this way?

The political cycle is speeding up - that hurts Labour now, but there’s no guarantee that it’s going to slow down. Look at the how quickly “reverse shift” has occured on the 2020-2024 graph. Is this sped up cycle a good thing for long term governance? Or does good governance slow it down? That was a piece of feedback on this blog from the excellent Rachel Woolf. The “reverse shift” is happening at a unprecedented pace - polling patron Sir John Curtice thinks that the fundamentals and polling numbers have degraded faster than ever before for Labour - but I’m not convinced that this is all about Labour, but about something more fundamental.

The aggregate right vote share will probably increase over the next couple of years. There’s trapped demand for more right wing politics on the economy (the next substack is about this) - but events matter and can still create chaos and unpredictable change. There’s no guarantee the loop just keeps running. See the movements 2016-2019.

Block dominance dynamics may continue to not advantage either Labour nor the Conservatives over the next couple of years, even beyond that. That would be consistent with the idea that we are in the “Reverse shift” phase. Some of the recent by-elections indicate real Reform presence on the ground. Next year's local elections could prove a pivotal moment.

It appears that as one block gets more “efficient” the other can keep up (that’s when movement is across the graph). That implies that even if Labour begins to leak votes to the Liberals, Greens (or SNP) that doesn’t imply that Conservative lead over Reform will improve in the short term - look how long it remains flat and travels horizontally during the past two cycles.

It does seem that once the public have reached an “end state” in terms of expressing a aggregate right or left vote share, the public does then self-sort to achieve the political outcome that they - in aggregate - want. This may sound like delayed good news for the Conservatives - but here’s the thing, Reform’s vote share and positioning is much more threatening to the Conservatives, than the Liberals were to Labour - except for that mad period of the 2019 European elections. Does there exist a world in which Reform become the main right party? This framework - again it’s a loose and informal one - does suggest that the public when they are ready to vote right again will find a way of doing so. But what’s the Conservative bargaining position with Reform’s voters when they do?

But related to that, what if we get Romulus and Remus with Reform and the Conservatives - will the public know how to self-sort? How does the centre-right get back onto “the ladder?” How do you get “block” dominance if, on the a first past the post basis, historic elections, and local election performance it simply isn’t clear who takes the lead and where? The concept of block/cohort dominance only makes sense if there is a senior political partner.

Next time?

The 2nd substack is going to take a look at the shift right happening on non-voting intention polling numbers in the U.K. There’s been lots of discussion about social issues, but I think we’re beginning to see the trace elements of a increase in support for lower taxes, free markets and other clusters of beliefs.

My third substack is going to be a deepdive into the Liberal Democrats and their vote patterns.

An interesting approach. It would also be interesting to examine the rise of and the effect of social media with regard to voting intentions as against 'natural' affiliations and aspirations. Are voters naturally more volatile and prone to psychological pressures. I feel a few PhDs in the offing.

"Thermostatic" - I must be missing something, but parties pivot around a perceived middle point, with voters switching to maintain policy around that preferred point?

Err, what? Overton Windows? Is this new?

Redo the charts, say '48 to '79, '79 to '10, '83 to '23, '90 to '20. Each is about 30 years - so generational timescales.

Does the loop, or it's timing, change?

Is it the parties (government - small g) that change, or the Government (BIG G) that changes?

Does G run out of options, requiring a shift in g, which is driven the voters, at a generational (30 year) lag?

Are there path dependencies here?